After creating a content management system (CMS) basic structure, and the actual server using Go and Node.js, you’re ready to try your hand at another language.

This time, I'm using the Ruby language to create the server. I have found that by creating the same program in multiple languages, you begin to get new insights on better ways to implement the program. You also see more ways to add functionality to the program. Let’s get started.

Setup and Loading the Libraries

To program in Ruby, you will need to have the latest version installed on your system. Many operating systems come pre-installed with Ruby these days (Linux and OS X), but they usually have an older version. This tutorial assumes that you have Ruby version 2.4.

The easiest way to upgrade to the latest version of ruby is to use RVM. To install RVM on Linux or Mac OS X, type the following in a terminal:

gpg --keyserver hkp://keys.gnupg.net --recv-keys 409B6B1796C275462A1703113804BB82D39DC0E3 curl -sSL https://get.rvm.io | bash -s stable

This will create a secure connection to download and install RVM. This installs the latest stable release of Ruby as well. You will have to reload your shell to finish the installation.

For Windows, you can download the Windows Ruby Installer. Currently, this package is up to Ruby 2.2.2, which is fine to run the libraries and scripts in this tutorial.

Once the Ruby language is properly installed, you can now install the libraries. Ruby, just like Go and Node, has a package manager for installing third-party libraries. In the terminal, type the following:

gem install sinatra gem install ruby-handlebars gem install kramdown gem install slim

This installs the Sinatra, Ruby Handlebars, Kramdown, and Slim libraries. Sinatra is a web application framework. Ruby Handlebars implements the Handlebars templating engine in Ruby. Kramdown is a Markdown to HTML converter. Slim is a Jade work-alike library, but it doesn’t include Jade’s macro definitions. Therefore, the macros used in the News and Blog post indexes are now normal Jade.

Creating the rubyPress.rb File

In the top directory, create the file rubyPress.rb and add the following code. I will comment about each section as it's added to the file.

# # Load the Libraries. # require 'sinatra' # http://www.sinatrarb.com/ require 'ruby-handlebars' # https://github.com/vincent-psarga/ruby-handlebars require 'kramdown' # http://kramdown.gettalong.org require 'slim' # http://slim-lang.com/ require 'json' require 'date'

The first thing to do is to load the libraries. Unlike with Node.js, these are not loaded into a variable. Ruby libraries add their functions to the program scope.

#

# Setup the Handlebars engine.

#

$hbs = Handlebars::Handlebars.new

#

# HandleBars Helper: date

#

# Description: This helper returns the current date

# based on the format given.

#

$hbs.register_helper('date') {|context, format|

now = Date.today

now.strftime(format)

}

#

# HandleBars Helper: cdate

#

# Description: This helper returns the given date

# based on the format given.

#

$hbs.register_helper('cdate') {|context, date, format|

day = Date.parse(date)

day.strftime(format)

}

#

# HandleBars Helper: save

#

# Description: This helper expects a

# "|" where the name

# is saved with the value for future

# expansions. It also returns the

# value directly.

#

$hbs.register_helper('save') {|context, name, text|

#

# If the text parameter isn't there, then it is the

# goPress format all combined into the name. Split it

# out. The parameters are not String objects.

# Therefore, they need converted first.

#

name = String.try_convert(name)

if name.count("|") > 0

parts = name.split('|')

name = parts[0]

text = parts[1]

end

#

# Register the new helper.

#

$hbs.register_helper(name) {|context, value|

text

}

#

# Return the text.

#

text

}

The Handlebars library gets initialized with the different helper functions defined. The helper functions defined are date, cdate, and save.

The date helper function takes the current date and time, and formats it according to the format string passed to the helper. cdate is similar except for passing the date first. The save helper allows you to specify a name and value. It creates a new helper with the name name and passes back the value. This allows you to create variables that are specified once and affect many locations. This function also takes the Go version, which expects a string with the name, ‘|’ as a separator, and value.

#

# Load Server Data.

#

$parts = {}

$parts = JSON.parse(File.read './server.json')

$styleDir = Dir.getwd + '/themes/styling/' + $parts['CurrentStyling']

$layoutDir = Dir.getwd + '/themes/layouts/' + $parts['CurrentLayout']

#

# Load the layouts and styles defaults.

#

$parts["layout"] = File.read $layoutDir + '/template.html'

$parts["404"] = File.read $styleDir + '/404.html'

$parts["footer"] = File.read $styleDir + '/footer.html'

$parts["header"] = File.read $styleDir + '/header.html'

$parts["sidebar"] = File.read $styleDir + '/sidebar.html'

#

# Load all the page parts in the parts directory.

#

Dir.entries($parts["Sitebase"] + '/parts/').select {|f|

if !File.directory? f

$parts[File.basename(f, ".*")] = File.read $parts["Sitebase"] + '/parts/' + f

end

}

#

# Setup server defaults:

#

port = $parts["ServerAddress"].split(":")[2]

set :port, port

The next part of the code is for loading the cacheable items of the web site. This is everything in the styles and layout for your theme, and the items in the parts sub-directory. A global variable, $parts, is first loaded from the server.json file. That information is then used to load the proper items for the layout and theme specified. The Handlebars template engine uses this information to fill out the templates.

#

# Define the routes for the CMS.

#

get '/' do

page "main"

end

get '/favicon.ico', :provides => 'ico' do

File.read "#{$parts['Sitebase']}/images/favicon.ico"

end

get '/stylesheets.css', :provides => 'css' do

File.read "#{$parts["Sitebase"]}/css/final/final.css"

end

get '/scripts.js', :provides => 'js' do

File.read "#{$parts["Sitebase"]}/js/final/final.js"

end

get '/images/:image', :provides => 'image' do

File.read "#{$parts['Sitebase']}/images/#{parms['image']}"

end

get '/posts/blogs/:blog' do

post 'blogs', params['blog'], 'index'

end

get '/posts/blogs/:blog/:post' do

post 'blogs', params['blog'], params['post']

end

get '/posts/news/:news' do

post 'news', params['news'], 'index'

end

get '/posts/news/:news/:post' do

post 'news', params['news'], params['post']

end

get '/:page' do

page params['page']

end

The next section contains the definitions for all the routes. Sinatra is a complete REST compliant server. But for this CMS, I will only use the get verb. Each route takes the items from the route to pass to the functions for producing the correct page. In Sinatra, a name preceded by a colon specifies a section of the route to pass to the route handler. These items are in a params hash table.

#

# Various functions used in the making of the server:

#

#

# Function: page

#

# Description: This function is for processing a page

# in the CMS.

#

# Inputs:

# pg The page name to lookup

#

def page(pg)

processPage $parts["layout"], "#{$parts["Sitebase"]}/pages/#{pg}"

end

The page function gets the name of a page from the route and passes the layout in the $parts variable along with the full path to the page file needed for the function processPage. The processPage function takes this information and creates the proper page, which it then returns. In Ruby, the output of the last function is the return value for the function.

#

# Function: post

#

# Description: This function is for processing a post type

# page in the CMS. All blog and news pages are

# post type pages.

#

# Inputs:

# type The type of the post

# cat The category of the post (blog, news)

# post The actual page of the post

#

def post(type, cat, post)

processPage $parts["layout"], "#{$parts["Sitebase"]}/posts/#{type}/#{cat}/#{post}"

end

The post function is just like the page function, except that it works for all post type pages. This function expects the post type, post category, and the post itself. These will create the address for the correct page to display.

#

# Function: figurePage

#

# Description: This function is to figure out the page

# type (ie: markdown, HTML, jade, etc), read

# the contents, and translate it to HTML.

#

# Inputs:

# page The address of the page

# without its extension.

#

def figurePage(page)

result = ""

if File.exist? page + ".html"

#

# It's an HTML file.

#

result = File.read page + ".html"

elsif File.exist? page + ".md"

#

# It's a markdown file.

#

result = Kramdown::Document.new(File.read page + ".md").to_html

#

# Fix the fancy quotes from Kramdown. It kills

# the Handlebars parser.

#

result.gsub!("“","\"")

result.gsub!("”","\"")

elsif File.exist? page + ".amber"

#

# It's a jade file. Slim doesn't support

# macros. Therefore, not as powerful as straight jade.

# Also, we have to render any Handlebars first

# since the Slim engine dies on them.

#

File.write("./tmp.txt",$hbs.compile(File.read page + ".amber").call($parts))

result = Slim::Template.new("./tmp.txt").render()

else

#

# Doesn't exist. Give the 404 page.

#

result = $parts["404"]

end

#

# Return the results.

#

return result

end

The figurePage function uses the processPage function to read the page content from the file system. This function receives the complete path to the file without the extension. figurePage then tests for a file with the given name with the html extension for reading an HTML file. The second choice is for a md extension for a Markdown file.

Lastly, it checks for an amber extension for a Jade file. Remember: Amber is the name of the library for processing Jade syntax files in Go. I kept it the same for inter-functionality. An HTML file is simply passed back, while all Markdown and Jade files get converted to HTML before passing back.

If a file isn’t found, the user will receive the 404 page. This way, your “page not found” page looks just like any other page except for the contents.

# # Function: processPage # # Description: The function processes a page by getting # its contents, combining with all the page # parts using Handlebars, and processing the # shortcodes. # # Inputs: # layout The layout structure for the page # page The complete path to the desired # page without its extension. # def processPage(layout, page) # # Get the page contents and name. # $parts["content"] = figurePage page $parts["PageName"] = File.basename page # # Run the page through Handlebars engine. # begin pageHB = $hbs.compile(layout).call($parts) rescue pageHB = " Render Error " end # # Run the page through the shortcodes processor. # pageSH = processShortCodes pageHB # # Run the page through the Handlebar engine again. # begin pageFinal = $hbs.compile(pageSH).call($parts) rescue pageFinal = " Render Error " + pageSH end # # Return the results. # return pageFinal end

The processPage function performs all the template expansions on the page data. It starts by calling the figurePage function to get the page’s contents. It then processes the layout passed to it with Handlebars to expand the template.

Then the processShortCode function will find and process all the shortcodes in the page. The results are then passed to Handlebars for a second time to process any macros left by the shortcodes. The user receives the final results.

#

# Function: processShortCodes

#

# Description: This function takes the page and processes

# all of the shortcodes in the page.

#

# Inputs:

# page The contents of the page to

# process.

#

def processShortCodes(page)

#

# Initialize the result variable for returning.

#

result = ""

#

# Find the first shortcode

#

scregFind = /\-\[([^\]]*)\]\-/

match1 = scregFind.match(page)

if match1 != nil

#

# We found one! get the text before it

# into the result variable and initialize

# the name, param, and contents variables.

#

name = ""

param = ""

contents = ""

nameLine = match1[1]

loc1 = scregFind =~ page

result = page[0, loc1]

#

# Separate out the nameLine into a shortcode

# name and parameters.

#

match2 = /(\w+)(.*)*/.match(nameLine)

if match2.length == 2

#

# Just a name was found.

#

name = match2[1]

else

#

# A name and parameter were found.

#

name = match2[1]

param = match2[2]

end

#

# Find the closing shortcode

#

rest = page[loc1+match1[0].length, page.length]

regEnd = Regexp.new("\\-\\[\\/#{name}\\]\\-")

match3 = regEnd.match(rest)

if match3 != nil

#

# Get the contents the tags enclose.

#

loc2 = regEnd =~ rest

contents = rest[0, loc2]

#

# Search the contents for shortcodes.

#

contents = processShortCodes(contents)

#

# If the shortcode exists, run it and include

# the results. Otherwise, add the contents to

# the result.

#

if $shortcodes.include?(name)

result += $shortcodes[name].call(param, contents)

else

result += contents

end

#

# process the shortcodes in the rest of the

# page.

#

rest = rest[loc2 + match3[0].length, page.length]

result += processShortCodes(rest)

else

#

# There wasn't a closure. Therefore, just

# send the page back.

#

result = page

end

else

#

# No shortcodes. Just return the page.

#

result = page

end

return result

end

The processShortCodes function takes the text given, finds each shortcode, and runs the specified shortcode with the arguments and contents of the shortcode. I use the shortcode routine to process the contents for shortcodes as well.

A shortcode is an HTML-like tag that uses -[ and ]- to delimit the opening tag and -[/ and ]- the closing tag. The opening tag contains the parameters for the shortcode as well. Therefore, an example shortcode would be:

-[box]- This is inside a box. -[/box]-

This shortcode defines the box shortcode without any parameters with the contents of <p>This is inside a box.</p>. The box shortcode wraps the contents in the appropriate HTML to produce a box around the text with the text centered in the box. If you later want to change how the box is rendered, you only have to change the definition of the shortcode. This saves a lot of work.

#

# Data Structure: $shortcodes

#

# Description: This data structure contains all

# the valid shortcodes names and the

# function. All shortcodes should

# receive the arguments and the

# that the shortcode encompasses.

#

$shortcodes = {

"box" => lambda { |args, contents|

return("#{contents}")

},

'Column1'=> lambda { |args, contents|

return("#{contents}")

},

'Column2' => lambda { |args, contents|

return("#{contents}")

},

'Column1of3' => lambda { |args, contents|

return("#{contents}")

},

'Column2of3' => lambda { |args, contents|

return("#{contents}")

},

'Column3of3' => lambda { |args, contents|

return("#{contents}")

},

'php' => lambda { |args, contents|

return("#{contents}")

},

'js' => lambda { |args, contents|

return("#{contents}")

},

"html" => lambda { |args, contents|

return("#{contents}")

},

'css' => lambda {|args, contents|

return("#{contents}")

}

}

The last thing in the file is the $shortcodes hash table containing the shortcode routines. These are simple shortcodes, but you can create other shortcodes to be as complex as you want.

All shortcodes have to accept two parameters: args and contents. These strings contain the parameters of the shortcode and the contents the shortcodes surround. Since the shortcodes are inside a hash table, I used a lambda function to define them. A lambda function is a function without a name. The only way to run these functions is from the hash array.

Running the Server

Once you have created the rubyPress.rb file with the above contents, you can run the server with:

ruby rubyPress.rb

Since the Sinatra framework works with the Ruby on Rails Rack structure, you can use Pow to run the server. Pow will set up your system’s host files for running your server locally the same as it would from a hosted site. You can install Pow with Powder using the following commands in the command line:

gem install powder powder install

Powder is a command-line routine for managing Pow sites on your computer. To get Pow to see your site, you have to create a soft link to your project directory in the ~/.pow directory. If the server is in the /Users/test/Documents/rubyPress directory, you would execute the following commands:

cd ~/.pow ln -s /Users/test/Documents/rubyPress rubyPress

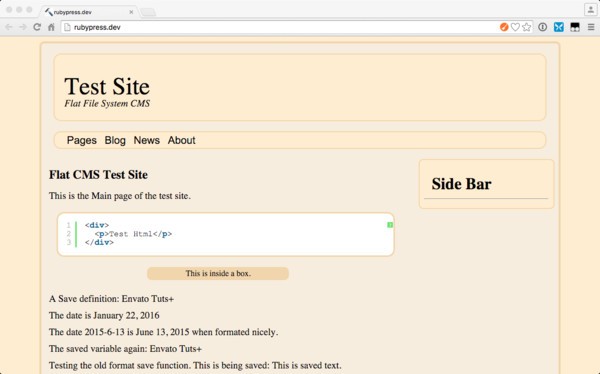

The ln -s creates a soft link to the directory specified first, with the name specified secondly. Pow will then set up a domain on your system with the name of the soft link. In the above example, going to the web site http://rubyPress.dev in the browser will load the page from the server.

To start the server, type the following after creating the soft link:

powder start

To reload the server after making some code changes, type the following:

powder restart

Going to the website in the browser will result in the above picture. Pow will set up the site at http://rubyPress.dev. No matter which method you use to launch the site, you will see the same resulting page.

Conclusion

Well, you have done it. Another CMS, but this time in Ruby. This version is the shortest version of all the CMSs created in this series. Experiment with the code and see how you can extend this basic framework.

Comments